Fort Collins in the 1940s: Historic Contexts

Woolworths, corner of College and Mountain

Fort Collins, Boulder, and Greeley in 1940: Comparisons

Effects of World War II on the West, Colorado and Fort Collins

Women and Ethnic Groups in Fort Collins

The Colorado Big-Thompson Project

Colorado State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts

Agriculture

Manufacturing

Retail and Small Business

Professional Businesses

Other Businesses

Tourism and Transportation

Hotels and Motels

News Media

City Infrastructure

Summary

Bibliography

FORT COLLINS, BOULDER, AND GREELEY IN 1940: COMPARISONS

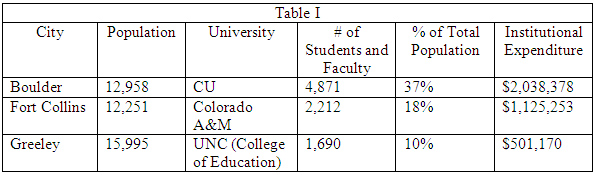

In 1940 Fort Collins, Boulder, and Greeley were similar in population: approximately 16,000 (Greeley), 13,000 (Boulder), and 12,251 (Fort Collins). Despite their close proximity the three were already showing elements distinguishing one from the other as exemplified by the WPA Colorado: a Guide to the Highest State, published in 1941. The description of Boulder focuses upon the University of Colorado, stating that Upon the university. the city depends for its livelihood, its sports, and its social and cultural life. Higher education statistics in the 1941-1942 Year Book of the State of Colorado reinforce this statement. When one considers the combination of student and faculty numbers with expenditures for each institution vis-à-vis overall population, the University of Colorado clearly had a disproportionate effect upon Boulder compared to the other two cities.

Conversely, the WPA Guide describes Fort Collins in terms of an economy largely based on produce grown in the surrounding agricultural territory. Significantly perhaps, the listing of Points of Interest in the town concentrates upon public institutions: the college, the Carnegie Public Library, and the county courthouse. The chapter on Greeley provides a history of the Union Colony, with an economic life. based on the fertile soils of these river valleys. The Points of Interest include not only the State College of Education, but also the Great Western Beet Sugar Factory.

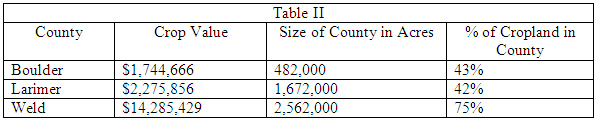

Basic agricultural statistics for Boulder, Larimer, and Weld counties also indicate a concentration in agriculture opposite that of higher education. A comparison among the three counties for crop values and percentage of farmlands in 1940 indicates the preponderance of agriculture in Weld County compared to the other two counties.

These figures are even more dramatic when one considers that the relative square miles of each of the three counties gave Larimer over three times the acreage of Boulder County, while Weld County, with its great size, possessed nearly three times the acreage of Larimer and almost ten times that of Boulder County.

These statistics indicate that Fort Collins, Boulder, and Greeley each had a mix of higher education and agricultural sectors that shaped the three Northern Colorado communities in the late 19 th and early 20 th centuries. The addition of manufacturing, government agencies, and technology components to the economies of the three communities after the Second World War would create a new look to each.

SOURCES:

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1941-1942.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Colorado Agricultural Statistics, 1940.

Polk's Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

US Bureau of the Census. 16th Census, 1940.

WPA Guide to 1930s Colorado.

EFFECTS OF WORLD WAR II ON THE WEST, COLORADO AND FORT COLLINS

Historians agree that World War II changed the American West as had no previous event since the gold rushes of the 1800s. The effect was greatest on the West Coast, where there was a concentration of large cities and war manufacturing plants and activities, but Colorado and its communities saw change as well.

At the beginning of the war the American West still found itself in a colonial status, with a small population engaged in producing raw materials such as minerals for capitalists and consumers elsewhere. The war began to change this status, with population growth fueled by workers moving west to take advantage of war industries, military personnel seeing the region for the first time, towns becoming cities, and greater ethnic diversity. Those who came often stayed or returned. Nevertheless, the Rocky Mountains, including Colorado, saw less immediate change than the Pacific Coast or the states of the Southwest. Between 1940 and 1950 the population of Colorado grew by 18%, well below the 25%, 40%, and even 50% posted by the Pacific Coast and Southwest states. According to historian Gerald Nash, Colorado might have seen greater advances had the Denver business community shaken off its traditional conservatism. Still, the seeds were planted for new ideas and activities. For example, pure and applied science migrated westward during the war, particularly in support of the secret activity of creating the atomic bomb. Science flourished on the West Coast, but in later decades the Front Range would begin to cultivate the scientific community and its institutions.

Gerald Nash, in two books on the American West in World War II, summarizes the economic changes wrought by the war, changes which were ongoing for the next several decades. He found that the increased population created new markets and a service sector that included tourism, education, healthcare, and financial institutions. The traditional economic base of agriculture and mining was supplemented by manufacturing and fabrication of raw materials, chemicals and petroleum among them. Many of the military bases established during the war remained in place afterwards and were accompanied by the defense industry. Finally, the emphasis upon science during the war eventually evolved into technology industries. Economically the American West would be much different than it was before World War II.

SOURCES:

Nash. The American West Transformed.

Nash. World War II and the West: Reshaping the Economy.

Locally, the war had immediate effects in both Colorado and Fort Collins. About 139,000 Coloradans served in the armed forces and 2,700 were among those who gave their lives. Training facilities for the massive number of service personnel were obviously a necessary component of the war effort, and Peterson Air Field (Colorado Springs), Pueblo Army Air Base, Camp Carson (Colorado Springs), Lowry Field (Denver), and Fitzsimons General Hospital (Denver), were among the major military installations established in the state. Fort Collins contributed through the State College of Agriculture, which trained members of the quartermaster corps. War manufacturing was concentrated in Denver, home not only to the Denver Ordnance Plant and the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, but also the great majority of Colorado companies contributing to war production. None of significance was located in Fort Collins. On the other hand, Colorado A & M physicist Philip G. Koontz contributed to the war effort by working on the atomic bomb project in both Chicago and New Mexico; other college faculty and students also took part in that program.

If military bases and manufacturing bypassed Fort Collins, residents of the town had other ways to contribute. Sales of war bonds eventually amounted to $15.4 million in Larimer County, while Weld County purchased $21.8 million and Boulder County $20.2 million. Rationing became a customary part of everyday life, with tires, automobiles, typewriters, bicycles, rubber footwear, coffee, and certain food items among those goods apportioned. Rent controls were established in a number of communities, including Fort Collins. Conservation and salvage efforts reached out to deal with scrap metal, wastepaper, tin cans, used household fats, rags, and even silk stockings and tin tubes. Voluntary activities included air raid wardens, victory gardens, and the United Service Organizations (USO).

SOURCES:

A & M Scientist among First 20 to Work on Atomic Bomb.

Hafen, Colorado and Its People. Volume 1.

WOMEN AND ETHNIC GROUPS IN FORT COLLINS

Statistics found in the 1940 U.S. Census indicate a social pattern yet to change. Of the 5,193 females 14 years old and over somewhat less than 25% (1,271) were in the labor force. Those engaged in own home housework (2,955) outnumbered those in the labor force by considerably more than 2 to 1.

That social pattern began to change in World War II, which witnessed the success of Rosie the Riveter. Women entered the workplace as replacements for men who went off to war. This phenomenon had its greatest impact on the West Coast, home to large shipbuilding and air manufacturing plants. In Fort Collins such opportunities were naturally limited. Some Fort Collins women probably moved out of town or out of state to take advantage of these employment opportunities, while others certainly joined the WACS and WAVES to serve their country in uniform. The idea of women performing civilian and military tasks similar to men would not fade, however, either locally or nationally.

The Hispanic community in the West continued to face discriminatory practices. Even their numbers were a matter of dispute; a federal estimate in 1943 found a minimum of 30,000 Hispanics in Colorado urban areas, particularly Denver, and another 120,000 in rural areas. (The total population of the state that year was a little under 1.2 million.) In Fort Collins, as elsewhere, this ethnic group was largely confined to specific neighborhoods: Andersonville, Alta Vista, Buckingham, and Holy Family, with all but the latter located north of the river. Basic services and utilities available to the Anglo population were often missing in these neighborhoods. In a presentation in 2002, for example, Daniel Martinez recalled specific instances of discrimination in restaurants, ice cream parlors, and movie theaters in Fort Collins in the 1930s and 1940s. Many older Hispanic people from rural backgrounds were accustomed to deprivation and made no protest, but younger Hispanics began to think differently. Attempting to find better paying jobs away from the sugar beet fields and in the cities, they found themselves subject to familiar barriers in terms of pay and housing. Federal agencies attempted to address these issues. Although their successes were limited these agencies did begin to institutionalize government concern with minority groups. Equally important, Hispanic military veterans returned to find themselves still in a discriminatory environment, one that they were less willing to accept as a result of their service to their country. Later sources indicate they used Alonzo Martinez American Legion Post Number 187 as a catalyst to begin agitation against merchants with white trade only signs. Finally, according to Adam Thomas and Timothy Smith, the construction of Horsetooth Reservoir and other facilities associated with the Colorado-Big Thompson Project provided Hispanic workers with labor and training for skilled and semi-skilled labor, thereby providing a path away from field work.

The Germans from Russia represented the only other significant ethnic group in Fort Collins. During the Second World War they faced less discrimination than in World War I. Membership in the armed services followed by access to the G.I. Bill of Rights enabled younger Germans from Russia to move into careers away from the beet fields and to purchase homes apart from their traditional neighborhoods. In short, the acculturation of the Germans from Russia to the mainstream society gradually ended their separateness from the Fort Collins community.

SOURCES:

Martinez. Growing up Hispanic in Fort Collins, Colorado.

Nash. The American West Transformed.

Thomas. Hang Your Wagon to a Star.

Thomas. Work Renders Life Sweet.

Thomas and Smith. The Sugar Factory Neighborhoods.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. 16 th Census. 1940.

THE COLORADO-BIG THOMPSON PROJECT

Wartime priorities and labor shortages hampered the progress of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project throughout the first half of the decade. The Project itself was massive, involving construction of nearly a dozen dams on both sides of the Continental Divide as well as a tunnel beneath Rocky Mountain National Park to divert water from the Western Slope to the Front Range. Project managers persisted, however, and on June 23, 1947, the Alva B. Adams Tunnel officially opened, with the resulting water channeled into the Big Thompson River for irrigation. Water for municipal purposes was an obvious future benefit and in 1948 Fort Collins applied for an additional allotment of 3,000 acre feet. Horsetooth Reservoir just west of the city got underway in 1946 when contracts were let for the necessary dams: Horsetooth, Soldier Canyon, Spring Canyon, and Dixon Canyon.

As part of Colorado-Big Thompson, The Bureau of Reclamation in 1946 leased a parcel of land near the intersection of McKinley Street and Laporte Avenue, where it constructed 35 prefabricated homes as well as office buildings for the Project. Here it would house workers in close proximity to the site for the Horsetooth dams. This development became known as Reclamation Village.

SOURCES:

Harris. Fort Collins E-X-P-A-N-D-S.

Tyler. The Last Water Hole in the West.

COLORADO STATE COLLEGE OF AGRICULTURE AND MECHANIC ARTS

World War II had a dramatic impact on Colorado A & M, initially in terms of enrollment demographics. By 1943-44 enrollment had dropped to 701, fewer than half from the year before. Women outnumbered men for the first time in school history. Another dramatic change began at that time; the college hosted military training programs for pilots, clerical staff, Army engineers, and veterinarians. These trainees numbered as many as 1,500 soldiers in uniform. The only existing dormitory was for women, so temporary living space was provided in other facilities on campus, including the Men’s Gymnasium. In addition, two hotels, the Armstrong and the Northern, were leased as barracks.

These activities were similar to those of other colleges and universities around the U.S., particularly those with a land-grant mission. Plus, the war created additional massive impacts on higher education. The G.I. Bill enabled veterans to attend colleges and universities at government expense. By the 1946-47 academic year at A & M, 2,500 veterans were in attendance out of a total enrollment of 3,500. Their numbers overwhelmed traditional housing, so with federal funding the college erected a Veterans Village of Quonset huts located adjacent to Laurel Street on campus between Loomis and Shields. The Quonset hut community featured dusty streets, children, and lines of laundry that collectively lacked aesthetic qualities and dismayed nearby neighborhoods. Only the construction of dormitories in ensuing years would ease the crunch in student housing.

SOURCES:

Hansen. Democracy‘s College.

Thomas. Soldiers of the Sword, Soldiers of the Ploughshare.

AGRICULTURE

Colorado crop production increased markedly during the war years, contributing to the nation’s food needs, but costs went up also, with a shortage of labor and consequent higher wages making themselves felt. Although farm acreage in Larimer County tripled from 1940 to 1945 the county maintained its relative ranking of approximately 20 th place in acreage among all counties in Colorado.

Overall during the 1940s sugar beets, a major activity in the agricultural sector of the local economy, held its own, while another, lamb feeding, saw a sharp decline.

Although the crop value of sugar beets in Larimer County increased from 28% of all crop values in 1940 to 47% by 1949, other measures were less impressive. The 1940 value of the sugar beet crop was $626,411, while in 1950 the value was $1,782,733. When inflation is factored in, the latter figure becomes $1,078,322 (1940 dollar value) in 1950, not quite twice the value 10 years earlier. Planted sugar beet acreage dropped from 12,294 in 1940 to 10,348 in 1949. Narratives of the beet sugar industry also paint an industry in flux. The 1938 Jones-Costigan Sugar Act aided the industry during the war but created a rigid price structure afterwards. Drought and increasingly expensive or nonexistent labor further exacerbated the situation. On the other hand, increasing mechanization decreased the need for field labor.

Conversely, the feeding of lambs, hitherto an agricultural mainstay, dropped precipitously. In 1940 179,000 lambs were in transit in the county, but by 1950 the number was down to 76,000. The Colorado Agricultural Statistics volume for 1950 attributed the decline on restrictions in the use of public lands and the fact that cattle have proven a more profitable ranch enterprise. It seems equally likely that changing food habits of Americans in conjunction with more use of cotton and synthetic fabrics was manifesting itself in the lamb and wool market.

The more successful fruit growing counties in Colorado were all located on the Western Slope, with one exception. Larimer County, in 1950, easily led the state in production preceding year bushels for cherries with a figure of 27,248,500, somewhat more than half the entire state production that year. Cherry trees bearing fruit numbered 154,679. On the other hand, production of apples in the county was miniscule compared to elsewhere in the state. Furthermore, production of the remaining commercial fruit crops (peaches, pears, and sweet cherries) was confined to the Western Slope.

Other statistics showed a certain amount of agricultural stability in the county. The percentage of farmland in Larimer County in 1940 was 42%; by 1949 this had risen to 45%. Likewise, the average farm size rose from 389 acres to 430. Reported hired farm labor, however, dropped from 634 persons over 14 in 1940 to 605 a decade later, although the latter figure lacked an age breakdown. In both cases it is possible that not all hired farm labor was reported for one reason or another, but mechanization, particularly in the beet sugar industry, also reduced the need for field workers.

SOURCES:

Bureau Of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator.

Colorado Department of Agriculture. Colorado Agricultural Statistics. 1948/1949 and 1950 editions.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Colorado Agricultural Statistics. 1940 and 1943 editions.

Hamilton. Footprints in the Sugar.

Twitty. Silver Wedge.

MANUFACTURING

The 1948-1950 ColoradoYear Book states that most manufacturing establishments were small in scale. In Larimer County in 1948 taxable payrolls for manufacturing were only marginally higher than those for retail trade ($825,000 compared to $747,000). In 1947 the 57 manufacturing plants in the county hired 1,035 employees. Although data for individual plants is not readily available, it is notable that the 17 beet sugar plants in Colorado employed a total of 2,516 people. Extrapolating from that figure it seems likely that the plants in Fort Collins and Loveland employed a total of 300 or more individuals. In other words, beet sugar manufacturing still represented a major component in the county manufacturing sector even while industry growth was uncertain. Colorado Portland Cement Co. (Ideal Cement) was probably another relatively large employer.

The flour milling industry, formerly a staple in Fort Collins, came to a demise in the 1940s. Hoffman Milling and Fort Collins Flour Mills, both listed in the 1938 City Directory, were out of the flour business by 1948, with Fort Collins Flour Mills switching production to animal feed that year.

A more specialized local industry was alabaster artwork. The WPA Guide to 1930s Colorado specifically mentions the production of alabaster art objects and the 1938 and 1948 city directories both list Fort Collins businesses specific to alabaster art. The Alabaster Company of America and the Rocky Mountain Alabaster Company both appeared in 1938, while the Cokely Alabaster Company, Pioneer Alabaster Company, and Ston-Art Company were listed in 1948. The families of Charles Roberts, Charles Douglass, and Roy W. Nye were prominent among the local alabaster operators of the 1930s and 1940s. In general this was a cottage industry operated out of homes, but the Roberts family at one point employed as many as 20 workers. Another well-known alabaster shop operated in nearby Loveland from 1933 through the 1970s. Owned by the Proctor family, it sold such items as lighthouses, salt and pepper shakers, and candleholders. As with others in the industry, the Proctors obtained their supply of alabaster from a quarry located at Owl Canyon. The WPA Guide mentions a second quarry operated by the American Onyx-Alabaster Company near The Forks. These two quarries were among the few commercial alabaster beds in North America.

A few well known family manufacturers merit a bit more attention. The Dreher family first opened a pickle curing plant in town in 1935, but in 1946 announced the construction of a pickle plant at the corner of Magnolia and Riverside to handle the cucumber harvest year-round. Agricultural operations in Oklahoma also contributed their crops, and the pickle factory was expected to employ between 50 and 60 full-time workers in addition to migrant labor during the harvest season. A cherry factory on Gregory Road was for a time owned by the Nugent family, who also operated a factory in Loveland. The Gregory Road factory apparently closed in the mid-1940s. Another locally noteworthy company, Forney Manufacturing, built a facility at 1830 Laporte in approximately 1943, signifying a long-term commitment despite the distractions of the war years. Finally, Charles Boettcher established a cement factory near the town of Laporte in 1927-28 following an antitrust suit that forced the closing of another of Boettcher’s cement operations. Although the company as a whole was named Ideal Cement, the Laporte plant officially was Colorado Portland Cement Company. Within a few years the establishment was employing as many as 90 men, and the industry flourished to such an extent that after World War II, Ideal established other plants and operations in Alabama, Louisiana, North Carolina, Oregon, California, and Utah. Colorado Portland therefore was perhaps the first manufacturing firm in Fort Collins to establish a national reach.

The initial edition of the Directory of Colorado Manufacturers appeared in 1948, providing a valuable picture of manufacturing in Fort Collins at the time. Listings for the town are few enough to be listed here. Parentheses denote product lines when company names are not otherwise apparent. Asterisks are explained below.

Boggs Candy Company*

Collander [sic; actually Collemer] Brothers Sawmill

Colorado Portland Cement Co.**

Colorado Printing Company

Dreher Pickle Company*

Forney Manufacturing Company [soldering equipment]

Fort Collins Brick & Tile**

Fort Collins Flour Mill*

Fort Collins Newspapers, Inc.

Fort Collins Packing Company*

Frink Creamery Co.*

Giddings Machine Company [agricultural machinery]

Great Western Sugar Company*

Heath Engineering Company, Inc. [storage tanks]

Iverson Dairy*

Long Publishing Company

Pioneer American Alabaster Company**

Poudre Valley Bottling Works*

Poudre Valley Creamery Co.*

Powers Brothers Cinder & Cement Block Company**

G. D. Richardson Manufacturing [canvas]

Riverside Ice & Storage Company*

Robinson Printing Company

Rogers Canning Company*

Seder & Son Molded Plastics Company

Spaulding Brothers Saw Mill

Listings with a single* denote those firms coded in the directories as dealing with Food and Kindred Products, while those with ** represent firms coded in Stone, Clay, and Glass Products. The codes therefore provide an indication of those manufacturing areas dominating the city and county.

Loveland possessed almost the same numbers in both these categories, although there are a couple of interesting contrasts between Fort Collins (1950 preliminary population 14,932) and Loveland (1950 preliminary population 6,759) in the food production sector. Loveland had five canned vegetable and fruit plants (Cherry Products, Kuner-Empson, Loveland Canning, E.G. Nugent & Son, Wolaver) compared to only one in Fort Collins (Rogers Canning). This presumably reflected a predominance in Loveland in regard to the cherry industry. Conversely, Fort Collins had four companies dealing with butter, ice cream, and/or cheese (Iverson Dairy, Poudre Valley Creamery, Riverside Ice & Storage, Frick Creamery) compared to only one for Loveland (Loveland Creamery). Possibly the concentration of dairy product companies in Fort Collins was a function of that community’s size vis-à-vis Loveland and its role as a business center for the immediate region. Also noteworthy is a comparison between the two towns in terms of stone, clay, and glass products. Fort Collins boasted Colorado Portland Cement [Ideal], Fort Collins Brick & Tile, Pioneer American Alabaster, and Powers Brothers Cinder & Cement Block. Loveland had to its credit Carver Novelty Shop, Proctors Alabaster, and US Gypsum. Sawmills are also worth a glance. Fort Collins had two: Collemer [erroneously spelled Collander in the 1948 Directory of Colorado Manufacturing ] Brothers and Spaulding Brothers, while elsewhere in the county the only commercial sawmill still in business was Griffith Lumber in Estes Park. Most sawmills elsewhere in the state were located on the Western Slope.

Of the 26 firms listed in the 1948 Directory most were located outside the town limits or on the northern edge of the community on streets such as Laporte, Riverside, North College, and North Mason. Only the printing establishments were in the city center.

SOURCES:

Bean. Charles Boettcher.

Cement Plant Important Now.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1940-1950.

Dreher Soon to Construct Building Here.

Fort Collins Local History Archive.

Ideal Cement Company $3,000,000 Plant to Open.

Jenson. Cherryhurst Gallery.

Loveland Museum.

Marmor. Carving a Living out of Stone.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

Steadman. The Dreher Pickle Company: a Home Grown Industry.

Swanson. Fort Collins Yesterdays.

University of Colorado Bureau of Business Research. 1948 Colorado Manufacturers Directory.

RETAIL AND SMALL BUSINESS

Second only to manufacturing in taxable payroll in 1948, retail trade represented a varied component of the Fort Collins economy. That year there were a total of 579 retail business stores in Larimer County as a whole. Proprietors and employees numbered 2,173, for an average of slightly fewer than four members of the work force in each establishment. In other words, small business dominated the scene.

Examination of the classified business directory section of the 1938 and 1948 city directories reveals the pattern of retail trade in the city:

| BUSINESS CATEGORY | 1938 | 1948 |

| Automobile Dealers (New) | 8 | 11 |

| Clothing, Retail | 6 | 11 |

| Department Stores | 4 | 6 |

| Druggists | 7 | 6 |

| Dry Goods | 3 | no listing |

| Grocers | 32 | 33 |

| Restaurants | 18 | 23 |

(Note: no city directories with classified business listings are known to exist between 1940 and 1948, making other annual comparisons unavailable.)

These figures can be examined not only in terms of numbers of business establishments, but also their locations and changes in directory listings and language. In 1938 the clothing, dry goods, and department stores were all located on the 100 blocks of Mountain and College, while the automobile dealers were almost all on the 200 and 300 blocks of the same streets. It is striking that a decade later in 1948 the concentration of these businesses continued to be almost the same; with a single exception the clothing and department stores were within a block of the intersection of Mountain and College, while the automobile dealers other than two agencies on the 100 block of West Oak remained on the 200 and 300 blocks. Although State Dry Goods retained its name, it was included in the category for department stores because the category for dry goods was eliminated from the directory. Not surprisingly, we also find that the number of automobile dealers, clothing, and department stores all increased in number in 1948, but a listing for children and infants clothing now makes an appearance, added to the prior categories for men’s and women’s wear.

The number of druggists remained relatively static from 1938 to 1948, with all but one located in the College and Mountain 100 block. The exception was located near the college campus. Restaurants showed a somewhat similar pattern in terms of location, with most downtown and a couple serving the college community. By 1948 there were also several restaurants on North College, perhaps located there to serve automobile traffic along U.S. highways 87 and 287, and Colorado 14 before the roads diverged to send travelers to Cheyenne, Laramie, and Poudre Canyon.

Unlike other businesses grocers were widely scattered around the community rather than concentrated downtown. In most neighborhoods residents had to walk only a few blocks to shop at a small mom and pop grocery store.

PROFESSIONAL BUSINESSES

| BUSINESS CATEGORY | 1938 | 1948 |

| Banks | 2 | 2 |

| Physicians and Surgeons | 23 | 24 |

| Veterinarians | 2 | 1 |

First National Bank and Poudre Valley National Bank were the only banks in town in both 1938 and 1948 and were located at the corner of Mountain and College opposite one another. Offices for physicians also clustered downtown, with particular buildings as favorite addresses: Robertson Building, Central Block, State Block, Physicians Building, Trimble Building, and the Colorado Building among those listed. A single woman physician, Mrs. Olive Dickey, appeared in the directory in 1938 and 1948; apparently she was in practice with her husband Lawrence. The scarcity of veterinarians is remarkable, but perhaps others had offices in the rural parts of the county. Residents also had the option of taking their animals to the veterinary facilities at the college. In fact, when the Glover Hospital opened in 1950 it included not only separate areas for large and small animals, but also a comfortable waiting room for owners of small animals, who tended to visit more frequently in order to check up on the condition of their pets.

SOURCES:

Hansen. Chiron’s Time.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

OTHER BUSINESSES

| BUSINESS CATEGORY | 1938 | 1948 |

| Apartments | 13 | 15 |

| Barbers | 22 | 12 |

| Beauty Shops | 18 | 12 |

| Coal Dealers | 4 | 6 |

| Dressmakers | 11 | 2 |

| Motion Picture Theaters | 2 | 4 |

| Music Teachers | 9 | 11 |

| Shoe Repair | 9 | 6 |

Barbers tended to be located in Old Town or along College Avenue, while beauty shops were a bit more scattered around the community. In both cases at least a few entrepreneurs set up shop in the general vicinity of the college. The decline in numbers in both barbers and beauty shops cannot be readily explained. The decrease in dressmakers may indicate greater consumer spending for clothes off the rack at retailers.

Although some apartment buildings could be found in Old Town and downtown, others were located on Remington or near the college and perhaps catered to the campus population. Only one, the McCormick, was west of College Avenue, at the intersection of Mountain and Mason.

In 1938 there were two motion picture theaters in Fort Collins: America Theatre and Lyric Theatre. By 1948 they had been joined by the State and Trail theaters. All were located downtown.

Coal dealers, music teachers, and shoe repair represent lines of business significant at the time but facing an uncertain future.

CONSTRUCTION

In terms of taxable payroll in 1948 construction was well below manufacturing and retail trade and somewhat below service industries in the county. Nevertheless, construction showed a modest upward trend. In 1940 the value of building permits in Fort Collins was approximately $285,000. In 1949 that figure was $1,360,000. Adjusted for inflation the 1949 data becomes a less dramatic $484,500, about 60% more than at the beginning of the decade. Interestingly, although residential building permits in 1949 represented only 16% of all permits they accounted for 56% of the total value. Comparison of business directory listings in 1938 and 1948 shows an increase in general building contractors from 17 to 19, commensurate at most with population growth. All listings were for individuals rather than firms.

SOURCES:

Bureau Of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1940-1950.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

TOURISM AND TRANSPORTATION

In 1940 the WPA Guide stated that the tourist industry was the largest and most profitable in Colorado, grossing approximately $100 million annually. The onset of the war with its gasoline rationing and other priorities saw tourist travel in the western U.S. drop by as much as a third throughout the western U.S., but inquiries from soldiers stationed in Colorado encouraged the continuation of the state publicity bureau in hope of a quick recovery at the war's end.

Fort Collins had several tourist attractions in the vicinity, including the best known, Rocky Mountain National Park. Others, such as Big Thompson Canyon, Poudre Canyon, and Red Feather, featured fishing, camping, and small resorts.

Although Colorado Highway 14 in 1940 was paved only between Ault and Ted's Place, it was an exception to other highways in the area. U.S. Highway 34 was paved from the Kansas border across Rocky Mountains National Park (by way of Trail Ridge Road), while U.S. highways 287 (to Laramie) and 87 (to Cheyenne) were both surfaced at least as far as the Wyoming border.

Two railroads served the city for those traveling by rail. The Union Pacific had a passenger depot on Jefferson Street, while the passenger depot for the Colorado & Southern, a subsidiary of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, was located at the intersection of Mason and Laporte. A tiny C & S passenger depot was located at the college on the east side of the tracks about a block south of Laurel Street. Within Fort Collins the Municipal Railway provided connections as far west as Grandview Cemetery and south to Pitkin Street by way of College and Whedbee. The streetcars passed within a block or less of each of the three passenger depots, but whether those arriving in town by rail utilized the Municipal Railway is unknown.

Several bus lines served the town in 1938 and 1948 alike and provided either connections nationally or locally to destinations such as North Park. In 1938 all bus lines had a shared facility at 185 N. College, but by 1948 only two lines were at this address. Two others were at 170 S. College and a fifth on the 600 block of East Myrtle.

SOURCES:

Athearn. The Coloradans.

Fraser. Railroads in Colorado, 1858-1943.

Hansen. Colorado State University Main Campus, Ringing Grooves of Change.

Jessen. Fort Collins Depots.

Peyton. Last of the Birneys.

WPA Guide to 1930s Colorado.

HOTELS AND MOTELS

Statistics furnished by the Fort Collins Chamber of Commerce for the city directory in both 1938 in 1948 indicate there were six hotels with a total of 350 rooms. However, the directory listing itself in 1938 included 10 hotels, while the listing for 1948 numbered 13. Some hotels possibly catered to a local clientele of long-term renters rather than travelers. All hotels both years could be found either in Old Town or along College Avenue throughout the decade. The Armstrong, at 261 S. College, was the most distant from the railroad depots. The Armstrong and the Northern were perhaps the premier hotels in the town. Travelers arriving by railroad or bus line had at least three options for traveling to hotels around town: the Municipal Railway, two taxi services located downtown, or walking. The latter involved several blocks at most if the destination were a hotel. The mix of hotel guests in terms of commercial and professional travelers versus tourists is unknown.

Automobile travelers had the option of staying at a tourist camp or auto court rather than a traditional hotel. There were six such establishments in 1938 and eight a decade later. (One 1948 establishment, the South Side Motel, may have been among the first using that label.) None were in the downtown area but rather were located in the highway corridors through Fort Collins, particularly the northern and southern portions of College Avenue where federal highway traffic could be intercepted. For a number of years the city operated a tourist camp at City Park in cooperation with concessionaire Robert Lampton, but financial difficulties forced closure about 1940. The Paramount Cottage Camp just north of City Park provided an alternative. These establishments were a harbinger of tourist industry trends.

Auto travelers and residents alike had need for gasoline and other quick facilities for their vehicles, and in both 1938 and 1948 there were 32 gasoline stations in town to meet that need. Most were near downtown or along the highway corridors, but a few could be found in outlying neighborhoods. Only a handful had names that associated them with petroleum companies; Conoco predominated. Some of the automobile dealers were among those also offering gasoline.

SOURCES:

City of Fort Collins Landmark Preservation Commission. [Paramount Cottage Camp Restoration/Rehabilitation].

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1940-1950.

Fleming and McNeill. Fort Collins Then & Now.

Polk's Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

Tunner. Overview of the Fort Collins Park System.

NEWS MEDIA

For many years the single daily newspaper had been the Express-Courier. On April 29, 1945, it changed its name to The Coloradoan, the change taking place after Alfred Hill sold the Express-Courier to newspaper chain owner Merritt C. Speidel in 1937. Speidel supposedly preferred that his newspapers include the name of their state in the title; hence the change some years after the original sale.

No radio stations were located in the city in 1938, but by 1948 KCOL was in operation.

SOURCES:

Halverstadt. Newspapers Leave Imprint on Fort Collins.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory. 1938 and 1948 editions.

Watrous. History of Papers Recounted.

CITY INFRASTRUCTURE

In 1947 the city comprised 2.75 mi.², with 68 miles of streets, nine miles of which were paved. By 1948 the 541 parking meters collected almost $32,000 in the first eleven months of that calendar year. The Light and Power Department reached 4,500 residential customers and 1,000 that were commercial. In addition to the golf course and cemetery the town boasted four parks: Lincoln, Washington, City, and Fort Collins Mountain Park. The latter was located 36 miles up Poudre Canyon. The city payroll had 16 categories, of which the Electric Department, police and fire, water mains and maintenance, streets and alleys, and the Municipal Railroad comprised the larger portion. In 1946 voters approved a quarter of a million bond issue for sewage, with completion of the plant scheduled for 1948.

As with other Colorado communities, Fort Collins enjoyed a transportation balance, with relative newcomers (automobiles, buses, and trucks) supplementing the prior railroad and streetcar systems. Traffic jams were a thing of the future, and private automobiles provided easy access to mountain recreation areas as well as alleviating rural isolation. As automobiles more and more were to become the preferred means of transportation they would exert fundamental change not only upon streets and traffic, but also upon the layout of the city itself in terms of commercial, industrial, and residential districts.

SOURCES:

Fort Collins Local History Archive. Fort Collins Time Line 1940.

Hill. Colorado Urbanization and Planning Context.

Information, City of Fort Collins. Fort Collins Local History Archive Folder Fort Collins 1940-1950.

SUMMARY

The 1938 Polk’s City Directory listed eight automobile dealers in Fort Collins, all located near the downtown core, mostly along College and Mountain avenues, with none further away than the 300 block on either street. The 32 service stations, on the other hand, were more widely distributed, as one might expect in terms of convenience for automobile owners. Many were in or near the downtown core, but there were outliers as far away as the 1700 block of South College, the 800 block of North College, and the 1000 block of West Mountain. Among the approximately 34 grocery stores, several could be found downtown, but most were scattered around the neighborhoods. The small extent of the community can be visualized from the street addresses of directional grocers: East Side Grocery & Market (429 E. Magnolia), South Side Grocery (318 E. Pitkin), and West Side Grocery (700 W. Mountain). Restaurants and lunch rooms numbered 18, with the great majority concentrated downtown, although a few located some blocks to the south may have catered to the college trade.

Despite the impact of World War II and concomitant growth, the 1948 City Directory showed a very similar pattern. In the 1940s, then, Fort Collins featured an industrial area at the northern outskirts of the town, a commercial core downtown, a smattering of retail and service establishments near the college, and a highway system that channeled traffic through the center of town. Many basic services were within walking distance or no more than a very short automobile trip. Not until the 1950s would this traditional community physical framework experience rapidly burgeoning change.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

A & M Scientist among First 20 to Work on Atomic Bomb. Coloradoan. August 12, 1945. Page 1.

Athearn, Robert G. The Coloradans. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1976.

Bean, Geraldine B. Charles Boettcher, a Study in Pioneer Western Enterprise. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1976.

Cement Plant Important Now. Fort Collins Express-Courier [?]. (Date and page unknown.)

City of Fort Collins Landmark Preservation Commission. [Paramount Cottage Camp Restoration/Rehabilitation]. August 11, 2010 Staff Report.

City of Loveland Museum.

Colorado Department of Agriculture. Colorado Agricultural Statistics, 1948 and 1949. Denver: 1951.

Colorado Department of Agriculture. Colorado Agricultural Statistics, 1950. Denver: 1951.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Colorado Agricultural Statistics, 1940. Denver: 1941.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Colorado Agricultural Statistics, 1943 Final, 1944 Preliminary. Denver: 1945.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1941-1942. Colorado: 1942.

Colorado State Planning Commission. Year Book of the State of Colorado, 1948-1950. Colorado: 1951.

Dreher Soon to Construct Building Here. 1946. Fort Collins Express-Courier, Sept. 13, 1946. P. 1.

Fleming, Barbara, and Malcolm McNeill. Fort Collins Then and Now. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2010.

Fort Collins Local History Archive.

Fort Collins Local History Archive. Fort Collins Time Line 1940.

Fraser, Clayton B. Railroads in Colorado, 1858-1948. Denver: Colorado Historical Society, State Historic Preservation Office, 1998.

Hafen, LeRoy R. Colorado and Its People, Volume 1. New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Company, 1948.

Harris, Cindy, and Adam Thomas. Fort Collins E-X-P-A-N-D-S: The City‘s Postwar Development, 1945-1969. Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, November 2010 draft.

Halverstadt, Jeff. Newspapers Leave Imprint on Fort Collins. Triangle Review. April 16, 1980. Pages 1, 20.

Hamilton, Candy. Footprints in the Sugar, a History of the Great Western Sugar Company. Ontario, Oregon: Hamilton Bates Publishers, 2009.

Hansen, James E. Colorado State University Main Campus: Ringing Grooves of Change, 1870-1973. Ft. Collins: Colorado State University, 1974.

Hansen, James E. Democracy’s College in the Centennial State, a History of Colorado State University. Fort Collins: Colorado State University, 1977.

Hill, David R. Colorado Urbanization and Planning Context. Denver: Colorado Historical Society Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, 1984.

Ideal Cement Company $3,000,000 Plant to Open, Fort Collins Express-Courier, December 25, 1927, page 5.

Information, City of Fort Collins. [September 30, 1948?]. Fort Collins Local History Archive Folder Fort Collins 1940-1950.

Jenson, Barney. Cherryhurst Gallery. in Morris, Andrew J., ed. The History of Larimer County, Colorado. Fort Collins: Larimer County Heritage Association, 1985. Page 138.

Jessen, Kenneth. Fort Collins Depots. Triangle Review, February 25, 1979. Page 5.

Marmor, Jason. Carving a Living out of Stone: Colorado’s Innovative Depression-Era Alabaster Industry. Colorado Heritage. January/February 2011. Pages 22-31.

Martinez, Daniel. Growing up Hispanic in Fort Collins, Colorado. May 4, 2002. Fort Collins Local History Archive Oral History Collection.

Nash, Gerald D. The American West Transformed. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985.

Nash, Gerald D. World War II and the West: Reshaping the Economy. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1990.

Peyton, Ernest S., and Al Kilminster. Last of the Birneys. Colorado Rail Annual, No. 17. Golden: Colorado Railroad Museum, 1987. Pages 231-271.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory, 1938. Salt Lake City: R. L. Polk & Co., 1938.

Polk’s Fort Collins City Directory, 1948. Omaha: R. L. Polk & Co., 1948.

Steadman, Veda. The Dreher Pickle Company: a Home Grown Industry. The Fence Post. September 5, 1988, page 4-5.

Swanson, Evadene. Fort Collins Yesterdays. Fort Collins: Publishers George and Hildegarde Morgan, 1993.

Thomas, Adam. Hang Your Wagon to a Star: Hispanics in Fort Collins, 1900-2000 (State Historical Fund Project 01-02-065). Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, 2003.

Thomas, Adam. Soldiers of the Sword, Soldiers of the Ploughshare: Quonset Huts in the Fort Collins Urban Growth Area. Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, 2003.

Thomas, Adam. Work Renders Life Sweet: Germans from Russia in Fort Collins, 1900-2000 (State Historical Fund Project 01-02-065). Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, 2003.

Thomas, Adam, and Timothy Smith. The Sugar Factory Neighborhoods: Buckingham, Andersonville, Alta Vista (State Historical Fund Project 01-02-065). Ft. Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, 2003.

Tunner, Carol. An Overview of the Fort Collins Park System Emphasizing City Park As It Relates to the Development of the Community. Master’s Thesis. Fort Collins: Colorado State University, 1996.

Twitty, Eric. Silver Wedge: the Sugar Beet Industry in Fort Collins (State Historical Fund a Project 01-02-065). Fort Collins: City of Fort Collins Advance Planning Department, 2003.

Tyler, Dan. The Last Water Hole in the West. Niwot, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1992.

U.S. Bureau Of Labor Statistics. CPI Inflation Calculator.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Sixteenth Census of the United States: 1940. Washington DC: Government Printing Office, 1943.

University of Colorado Bureau of Business Research. 1948 Colorado Manufacturers Directory. Denver: Colorado Resources Development Council, 1940.

Watrous, David. History of Papers Recounted. Triangle Review. January 11, 1984. Pages 4, 6.

WPA Guide to 1930s Colorado. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 1987.