News Flashbacks

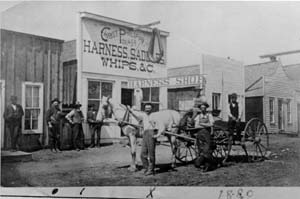

When Jefferson Street Was the Center of Things

By F.C. Grable

Fort Collins Express-Courier, July 12, 1934

Installment IV

"Your story of the old stage coach", said A.A. Edwards, "turned the clock back for me nearly sixty years; back to the late seventies, and to Jan. 1st, the calling day in society, better kept then than now."

"A few of us young men", continued Mr. Edwards, "concluded we would celebrate the occasion with a degree of ceremony coupled with some fun. So we cleaned up the Concord coach, tied some ribbons on it, and hitched four assorted horses to it of unusual shape and varied sizes. "Our lead team, we called the 'long and short' of it. One of them was the tallest horse we could find by scouring the county; and he was so thin he was just like a couple of planks boiled together; every rib being distinctly in evidence. His mate was a roly, poly pony, half as high, and as broad as high. Now, driving teams always have the biggest horse on the near-side; but to make it more grotesque we put our giraffe animal in the off-side. Our wheel horses were just as ridiculously matched; and there never was such a turn out probably before or since. But fun! We had it!

"Later, when I was back at my old home visiting," said Mr. Edwards, "I saw Buffalo Bill, Wild Bill, Texas Jack and a Dutch comedian, giving an entertainment at Sharon, Pa., the county seat of my home county of Mercer, which is where our "Mercer" irrigation ditch got its name. That was Buffalo Bill's first season as a traveling showman."

"Then in 1886 when I went east again, the Wild West show had been organized and I went to see it at Greenville, Pa. There I saw our old Concord coach thrilling the crowd, as it was driven furiously around the arena, filled with tourists to represent the frontier days; and attacked by the Indians who were beaten off by the government scouts arriving in the nick of time, led by Buffalo Bill who looked a picture on his white horse that shone with the care given it: the rider being a figure unequalled in gracefulness and dignity: his hair hanging to his shoulders, and his big sombrero waving to the crowd, wild with their enthusiastic cheering. It really was a noble show and made one feel proud of the west," concluded Mr. Edwards.

The storekeepers on Jefferson street were helped greatly by the tie business in the early days; hundreds of thousands of ties would be cut and floated down the Cache la Poudre river in the flood season. The men could cut every month of the year, but June was about the only month when the floods were great enough to bring the product to market; the rest of the time they would pile the ties on the edge of the river far up in the mountains to wait for the summer [thaw].

The choppers who came down the river with the rafts had to be in and out of the icy water from the time they started until they arrived here. They found out that the only way they could expose themselves to that ice-like water and ward off pneumonia was to dress in wollen underwear, from two to four suits at a time, and no outer clothing. That always made trouble for the workmen when they came into Fort Collins for the town marshal insisted they were not dressed according to civilized rules, and wanted to drive them out of town. But the men always had the sympathy and help of the Jefferson street merchants in their trouble.

The men would build barricades in the river to divert the ties from the stream to level land. Cribs built of small logs, filled with boulders, then planks spiked from one rib to another, would hold back the ties, but let the flood waters thru. The overflow would carry the ties away from the river where they could be piled up, counted and marketed.

They had a barricade about a mile above Laporte, and another here at Fort Collins just west of the concrete bridge on College avenue where they used the old bridge of the Colorado Central Railroad company, after the railroad abandoned it. The remains of those old time works are still in evidence. Chas. Pennock of Bellvue was one of the tie operators, bringing down as high as 20,000 in one drive. He got 45 cents apiece for them. That was before the days of the forest reserve supervision of the vast government domain and there was nothing paid for the pine trees of which the trees are made.

The tie business of our country is enormous. We have 250,000 miles of railroad in the United States and an average of 2600 ties are used to the mile. That would make 650,000,000. Formerly only oak material was even considered; but the country run out of oak timber which would make ties that would last 12 to 15 years; then came the use of pine, whose lasting qualities were only six or seven years; until creosoting was adopted which makes them last as long as oak, the [c]ost to the railroads being about $1.25 a tie.

In all the years since railroads came into existence, which is less than a century, nothing has been found to take the place of wood ties. Concrete has been tried, also metal, but each produces too solid a contact. The big engines weigh as much as 700,000 pounds, and when they go around a curve there has to be a little give under their terrific speed and tremendous weight.

Ties are made about 7 inches wide, 6 inches thick, and 7 feet long. They weigh around 85 pounds each, and 700 are loaded in a car. There are creosoting plants at Denver and Laramie, and a million ties must be piled up at the latter place ready for use.

Sam A. Thompson of Fort Collins has been making ties at Fox Park Colorado for thirty years. It was to his operating plant that a number of our citizens went last month, to see the interesting launching of the tie rafts down the river.

Preserving the history of Fort Collins, Colorado & the Cache la Poudre region